This is the text of an interview kindly hosted by Erin Al-Mehairi on ‘Oh, for the Hook of a Book‘

Talking with English Author Jenny Barden about Lost Colony of Roanoke and Writing History

Hi Jenny, welcome to Oh, for the Hook of a Book! I’m delighted to have you with us today to speak about your writing, specifically, your newest novel, The Lost Duchess, which just released TODAY in paperback! I am sure you are thrilled with the culmination of publishing this second book, but tell us some of the exciting endeavors you’ve been up to in preparation for its release?

Jenny: It’s lovely to be here talking to you, Erin. Thank you for inviting me over! The Lost Duchess comes out today, June 5, in paperbackand I’m in the midst of a string of appearances, interviews and a blog tour organized through HFVBT. The last talk I gave was at the Elizabethan Merchant’s House, Eastbury Manor, run by the National Trust, where I spoke about ‘Queens, Heroines and Heartache’ with Elizabeth Fremantle and Joanna Hickson. The next feature I’ll be posting will be on the Romantic Novelists’ Association blog titled ‘History and Love, how can we ever unravel the truth?’ That’ll come out this Friday. Those are just two examples of a long list of events I’m involved in. Life is a bit of a whirlwind at the moment!

Erin: The weather is heating up here on the East Coast of the U.S. at the time of this interview, but I’d still love to put on a pot of tea. I prefer Earl Grey, do you have a preference? Tell me what kind of tea you’d like, and how many sugars and if you’d like cream, and I’ll bring in a tray with some of the sugar cookies I baked yesterday as well.

Jenny: Oo, that’s wonderful! I adore tea and drink far too much of it when I’m writing. (Every time I get to the end of a scene or difficult paragraph that’s definitely an excuse for a cuppa!) I prefer PG tips, not very strong, plenty of milk and no sugar. ‘Babies tea’ is how some people describe it! Your cookies sound delicious. I’ve got a clear picture of them in my mind, and the smell… Yum. You’re too kind!

Erin: Now that we are all settled in, let’s begin our discussion! We’ll start with the gorgeous cover….

Q: The Lost Duchess is the second book in a sort of series, since it features a character’s relative from your previously published, Mistress of the Sea. However, it can be read as a stand-alone, correct? How do they fit together, if they do, for reading as a pair?

A: The Lost Duchess is a stand alone, that’s true, but if you read Mistress of the Sea you’ll find the hero of The Lost Duchess appears in that book too. The male lead in my first book is Will Doonan, and his brother, Kit, is held hostage by the Spaniards, taken prisoner, set to work in the mines of Panama, freed by escaped African slaves, and later becomes their leader. Kit takes one of these outlaws as his lover and fathers a son before being rescued by Will and returning to England. This mixed race love child and the fate of the child’s mother form part of the dark history that Kit carries with him into The Lost Duchess. To read both books in chronological order you might want to begin with Mistress of the Sea but if you’d rather go straight to the story about the Lost Colony then picking up The Lost Duchess first is fine. You won’t enjoy it any less for not having read the Mistress beforehand!

Q: The Lost Duchess takes the reader on a thrilling journey as the court of Elizabeth I sends Sir Walter Raleigh to sea on a mission to stake the first colony, or permanent settlement, of England in the New World. I’ve been intrigued by the lost colony of Roanoke since my teenage years. When and how did your interest first begin?

A: I first came across the Lost Colony story while researching the career of Francis Drake following on from his raid on the Spanish ‘Silver Train’ (the backdrop to Mistress of the Sea). In his biography of Drake, John Sugden wrote about how, when Drake returned from his sack of Santo Domingo in 1586, he stopped off along the coast of Virginia, looking for the men commanded by Ralph Lane who’d set up an English garrison in America under the patent of Sir Walter Raleigh. This was the first I’d heard of Roanoke and it piqued my curiosity. (When I was at school, most English kids weren’t taught about this episode in history, and still aren’t as far as I know.) Once I started looking into what had happened at Roanoke, I was hooked.

Q: Without giving any spoilers away, how did you tackle the mystery that surrounds Roanoke? How much research did you conduct, how did you conduct it, and further, how much is really known about it?

A: The mystery is truly fascinating, and the more I probed the more questions I uncovered. ‘Where did the Lost Colonists go and what became of them?’ That’s just the start. Why did the expedition leader behave so strangely? Was Simon Ferdinando really an agent of Spain or Walsingham? Why did he not take on fresh provisions when he had the chance? Why abandon the flyboat in the Bay of Biscay and two men on Puerto Rico? Why did he almost wreck the flagship by attempting to navigate a passage too far south? Why were the colonists not set down in Chesapeake Bay as originally planned? What happened to the fifteen men left by Sir Richard Grenville after Drake had evacuated the fort at Roanoke? Why did Wanchese, the leader of the Roanoke tribe, become so hostile when he’d been taken to England, treated well as a guest of Raleigh, and returned to his homeland in friendship? Why did Manteo, the leader of the Croatan tribe (afforded similar treatment) become a steadfast ally despite an English attack on his own tribe? Why did John White, artist, observer and expedition leader, leave his daughter and baby granddaughter behind on Roanoke apparently (so it would seem from his own account) more concerned about his records, possessions and reputation than with their safety? The questions go on. For a novelist, they’re wonderful material because there’s no need to manipulate history in order to produce an engrossing story; it’s there in the facts – the mystery remains unanswered.

As for my approach, I began by reading all the first-hand accounts and finding out as much about the history of the Lost Colony as I could, that included visiting Roanoke and the surrounding area and tracing the sites of nearby Algonquian Indian settlements. Then I used my research as a springboard for constructing the story. Quite simply, the story fills the gaps. One of the delights for me was to find how neatly the story gave a plausible explanation for all those questions I listed earlier, and many more besides. Of course The Lost Duchess is not meant to encapsulate a definitive truth, but I’ve tried not to take liberties with what actually happened as far as the historians agree, and to be faithful to the records that have survived.

Q: Have there been recent advances in learning the true mystery of Roanoke? Clues that lead historians and interested parties in a certain direction toward learning what happened to the settlers?

A:There have certainly been advances but none of them have so far provided an over-arching solution to the enigma, the advances have amounted more to a gradual accumulation of potentially relevant information. Take the discovery in 2012 of the icon for a fort under a patch on White’s Virginea Pars map. I know this has intrigued you, Erin. The patch appears over the confluence of the Chowan and Roanoke Rivers as marked on the map, and the icon was found using infra-red analysis and X ray spectroscopy at the British Museum. It led to speculation that perhaps this was where the colonists relocated. Recent remote sensing techniques and archeological work on the ground have suggested that there was indeed a settlement at that location long ago, but quite possibly an Indian settlement overlain by a later colonial settlement. There’s still no proof of any Elizabethan colonists having been there.

Taking into account the fragile geology of the Outer Banks and the Pamlico Sound, the volatility of the climate, and the shortage of stone as a building material, along with the biodegradable nature of most of the artefacts which the colonists would have used , it’s likely that few traces will be left. The site of the original City of Raleigh could now be under the Sound, a victim of hurricanes and erosion. If the Lost Colonists did not survive long following White’s departure then they probably wouldn’t have left much in the way of evidence of their time as settlers. Ongoing DNA analysis of possible descendants may well provide more clues, but the mixing of the gene pool over the generations will have made the process difficult, along with the problem of finding comparable samples in England reliably close to the colonists who left.

The answer to what actually happened may well be a mix of different scenarios. A group could have travelled north towards Chesapeake; another may have gone west, inland; some of the Lost Colonists could have been captured and held by native Indians; some may have married into local tribes and become assimilated; some may have formed a new colony; some may have been killed. Perhaps, even, some could have sailed away in the ocean-worthy pinnace which was left on Roanoke. I doubt we’ll ever know the whole truth.

Q: In The Lost Duchess, did you only rely on historical fact that you found and leave the mystery intact or did you come up with some solutions within your plot to engage readers? What kind of imaginative thoughts went into your process?

A: I relied on the historical facts, came up with solutions that I hoped readers would find both plausible and interesting, and left a few questions outstanding for readers to provide their own answers. What I had at the start of the process was an immense puzzle. I needed to solve it in order to begin writing, and there was a further level of complexity in that the solution had to support a story that was both credible and engaging. The amount of imagination used in the process was very high even though I had a factual backbone. The story is structured around a series of facts and hypotheses, but what makes it come alive is the recreation of time, place and personalities. Through the story I hope the reader will identify with Emme and Kit and experience with them something of what it must have been like to sail to Roanoke to start a new life and see the New World as one of the first colonists.

Q: Was it exciting to think up possibilities for historical questions left unanswered? How do you create “ideas” for history while still following historical fact? What do the best writers do “right” when they use this tactic to find supposed answers to unanswerable mysteries?

A: The process was hugely exciting. I think the business of coming up with ideas within the parameters of known fact is what makes writing historical fiction such an irresistible challenge. The really strange twist to all this is that I’ll delve and delve to uncover the truth – I mean the truth in the widest sense, not just pertaining to recorded events, but the truth about the way people lived and behaved, their beliefs attitudes, and everything relevant to their everyday existence, and then, having done all that, I’ll invent. I think, at its best, the process is almost magical: ideas spontaneously emerge and the story starts to tell itself. So I’ll read passages from John White’s account and I’ll hear him talking, look at his paintings and see his hand moving over the page; the characters come alive, I’m actually in the story and it’s all making sense. But what I could never do is invent first and add the facts later. I know some writers do that, but for me it just wouldn’t work. I have to be sure of my ground in order to invent with conviction!

Q: There is so much that happens in history during Elizabeth I’s reign that I feel many times most people forget that she began much of the intelligence movement, having many around her gathering information, as well as beginning the New World colonization. Why did she support global colonization? What was England’s purpose for gaining new ground?

A: Elizabeth’s spy network, led by Sir Francis Walsingham, was extremely sophisticated and invaluable to her in maintaining control. The fact that she was a woman, and thus less able to campaign at the head of an army, may well have had something to do with her reliance on intelligence to forestall any crisis. Through intelligence she formulated strategies to deal with threats both at home and abroad. Inevitably there were times when she had to take direct action, as in the execution of Mary of Scots and taking up arms against the Armada, but in general Elizabeth used wit rather than might to preserve her own position and the security of her realm. The gathering of intelligence was one of her methods, as was playing off her suitors, surrounding herself with clever loyal advisors, keeping everyone guessing as to her real intentions, and creating her own iconic image as Gloriana. The drive to colonize the New World was given impetus because of that; here was the Virgin Queen proving her place on the world stage by claiming a vast virgin land. Colonization was also driven by the desire for wealth, specifically gold and silver to rival the riches of the Aztec and Inca empires plundered by Spain. It was bound up with evangelical zeal, the urge to spread the message of the new English style of Protestant Christianity. There were other motives too: the itch to check Spanish expansion north along the eastern seaboard of America, and plain mischief-making on the part of Raleigh, Drake and other English seafarers who all enjoyed goading the Spaniards. Richard Hakluyt set out a plethora of reasons for England to colonize Virginia in his Discourse on Western Planting, and they include helping the wool trade because the Indians would need clothes! It’s a masterpiece of expansionist rhetoric.

Q: I like your use of Elizabeth I’s lady-in-waiting, Emme, as the protagonist. You created for readers an emotional tie with her from the start of the book, and then, allowed it to grow so that we could see life in the 1500s through her eyes. How did you develop her character while you wrote your book?

A: I’m glad you like Emme. She developed from the name ‘Emme Merrymoth’ who was listed in the records as one of the Lost Colonists though nothing else is known about her. I built up her identity from the fact that there’s a parish of Fifield-Merrymouth in Oxfordshire deriving, via ‘Merymowthe’ from the thirteenth century French name of ‘Murimuth’. So ‘Emme Merrymoth’ became ‘Emme Fifield’ in my book, daughter of the Baron of Fifield-Merymowthe, who assumes her family name of ‘Murimuth’ for Raleigh’s voyage, which is recorded in the manifest as ‘Merrymoth’ since Elizabethan spelling was done phonetically with little regard for consistency. I made her a lady-in-waiting to the Queen to take the reader into the heart of the Elizabethan court and so gain an insight into the wider background to the expedition. Her abuse at the hands of a nobleman leads to her wish to escape. I imagine that many of the real Lost Colonists probably had deep seated personal reasons for wanting to make a fresh start over the ocean, just as with many American settlers through the centuries since. There would have been the big picture involving the Queen and Raleigh which provided the opportunity, and there would have been a host of individual smaller pictures about which we know very little, though there are glimpses in the records such as John White’s journal. It’s within the smaller pictures that the essence of The Lost Duchess lies.

Q: How did you use detail and imagery to create feelings of excitement, dread, turmoil, and foreboding?

A: Detail and imagery are absolutely crucial to setting the mood of any scene. You’ve picked out a few feelings, and obviously other factors come into play in conveying these: accelerating pace to build up excitement; confusion in perception to suggest turmoil, and so on. To concentrate on detail and imagery, let me give you an example towards the end of the book, when Emme and Kit are travelling by boat towards Choanoke in a last ditch attempt to negotiate with Wanchese and save the Colony. The mood I wanted to create was one of apprehension, so I describe how Emme hears a strange sound: ‘A melancholic wave that endlessly rose and fell, though there was no one to be seen, and the nearest shore was so distant she could only just make out the trees at the water’s edge, rising straight from the haze of river mist, their roots bulging in mounds as if they had grown out from graves…’ This is an example of detail from direct observation. I’d been to the banks of the Chowan and I’d seen the bald cypress trees with their buttress roots and projecting ‘knees’ so they were clear in my mind. The mood of apprehension is strengthened by the imagery of the bulging root mounds which appear to Emme ‘like graves’, and there’s a sense of dislocation throughout. What she hears cannot be placed, the shore is indistinct, and the wave of sound never ceases. Cumulatively (I hope!) it all adds to a sense of mounting unease. Later on in this scene, after being told that the song is welcoming them back from the dead, Emme tries to sleep, and is given a string of pearls by Kit which he ties around her wrist. “Count the pearls until you reach the end,” he says. Then the story continues: ‘She smiled to herself at that, since now there was no end to the loop they had made. But that is what she did, running the pearls through her fingers one after the other, imagining arrows raining down like the shooting stars in the heavens, only to vanish as completely because she had the pearls in her grasp and each was full of the shielding power of his love…’

The pearls are a detail that is important. They’re purely a product of my imagination, inconsequential in themselves, but they make the story at this point because of what they represent and convey. Everyone should be able to identify with this scene. We’ll all have run our fingers over a bracelet in similar fashion, and counted to try and sleep. It’s by involving the reader in drawing from the detail that any story is really told – at least I think so!

Q: Who is your personal favorite member of history from this time period (Elizabeth I’s reign) and why?

A: That’s such a hard question to answer, and I’m going to protest that it’s unfair because whenever I focus on one of the greats from Elizabethan history I’m invariably fascinated and they become my favourite for as long as I’m studying them! So Drake was the tops while I was busy with Mistress of the Sea, then Raleigh became my favourite when I started The Lost Duchess, though I was captivated by Elizabeth too, and I admire her even more now that I’m working on my next book. But if I set aside the real characters who appear in my novels, then my favourite Elizabethan is most definitely William Shakespeare. I’d love to have known him!

Q: I read that you traveled from your home in England to the U.S. to research New World history. I really like that more writers are writing about this time period (in fact, my son and I are both writing novels featuring our ancestor who helped create Manhattan in the 1600s) because there is so much intertwining culture and a vast array of interesting mysteries and stories. Can you talk about the places you visited and where the best historical sites are for tourists or for writers researching?

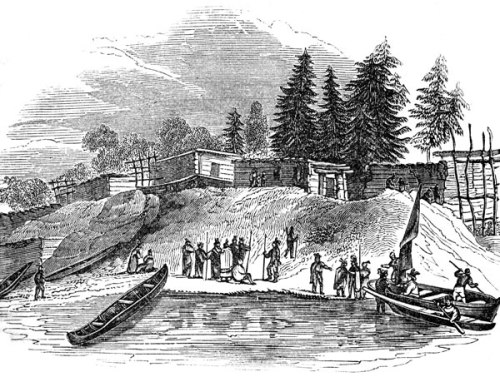

A: The novels you and your son are writing sound fascinating. It’s wonderful to make connections between the here and now and the past and find links to such traces as remain. For Roanoke there are obvious sites to visit for anyone interested, such as the Fort Raleigh National Historic Site and the excellent reconstructions at the Roanoke Island Festival Park. But I got most of my inspiration from travelling to fairly remote places around the Sound where there were no buildings, no cars, no people and no place names, from swamps to barren shores. I’ve put up a few pictures on a Pinterest Board and I’d be happy for you to share them here: http://www.pinterest.com/jennybardenuk/roanoke/.

Q: I’ve read a lot about how the Spanish explorers invaded Native American/First Peoples culture, but how did the English seem to get along with them? For readers, is it really like the sensationalized story of Pocahontas and John Smith? What was the British stance on treatment of Native American in forging colonies?

A: The first English settlers had a curiously mixed approach to indigenous peoples: a reflection of the contradictions inherent in their culture and beliefs at the time. The English were also inexperienced as colonists having settled little beyond the ‘plantations’ in Ireland, and I think the methods that had been used there set the seeds for disaster in Virginia. The seasoned soldier Ralph Lane, who was Roanoke’s first garrison commander, pursued a policy of harsh treatment and reprisal in the face of any opposition. By contrast, John white, along with expedition founders, Raleigh, Hakluyt and Thomas Harriot, advocated a policy of Christian kindliness and tolerance towards native American Indians whom they described as guileless ‘gentle savages’. The difficulties for White arose from the hatred engendered by the aggression of Lane’s earlier tactics. When White encountered hostility, his attempt at a punitive raid proved disastrous. This is putting the situation very simplistically. A legend has grown up around John Smith and Pocahontas but I’m sure that, twenty years earlier, the Lost Colonists faced a predicament that was just as dangerous and dramatic.

Q: Have you written any other books besides Mistress of the Sea and The Lost Duchess? What other writings do you have planned for the future?

A: Those novels are my first, and I’m now working on a story about a lady close to Queen Elizabeth at the time of the Spanish Armada.

Q: I know we had sugar cookies today, but what is your favorite tea time snack?

A: I’m very fond of dark chocolate coated ginger biscuits; have to say, they’re my downfall!

Q: Where can readers and writers connect with you?

A: My website is the best place for contacting me and keeping up with what I’m doing: http://www.jennybarden.com/. I love to hear from readers and writers, and if anyone would like to pop a question then please do so via my site contacts page – it’ll come straight through to me. I’d encourage anyone interested to subscribe to my blog posts: https://www.jennybarden.co.uk/jenny-bardens-blog/ I can also be followed on Twitter @jennywilldoit and on Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/jennybardenauthor

Erin: Thank you so very much, Jenny, for taking the time to answer my questions today. It’s been very interesting. I look forward to connecting and talking more in the future about the New World vs. Old World and especially to read any more books that you might write. Best wishes on wonderful success with The Lost Duchess.

Jenny: Thank you so much, Erin. It’s been an absolute delight to talk with you, I really appreciate your deep interest, and I hope you’ll ask me back for more cookies one day!

I hope you’ll also allow me to say how very grateful I am for your fabulous and perceptive review of The Lost Duchess. Thank you again.

Erin: Of course you may come back and I’ll whip up some cookies and you are most welcome for the posting. I’ve enjoyed them!

***

Erin’s review of The Lost Duchess may be found here: Jenny Barden’s The Lost Duchess Offers Plausible Solution to Lost Roanoke Mystery